Have you already bought domain names with your children’s names?

While recently purchasing yet more personal domain names to point to my website I was tempted to think about the future and therefore run a search for domain names with my children’s names. Some are still available, others not. So, should I buy the ones available and place alerts for the other ones just in case? Several of my friends had embarked on a purchasing frenzy as soon as their children were born, covering all imaginable combinations of domain names with their newborns’ names. Should I copy them? Or should I let life take its course?

While recently purchasing yet more personal domain names to point to my website I was tempted to think about the future and therefore run a search for domain names with my children’s names. Some are still available, others not. So, should I buy the ones available and place alerts for the other ones just in case? Several of my friends had embarked on a purchasing frenzy as soon as their children were born, covering all imaginable combinations of domain names with their newborns’ names. Should I copy them? Or should I let life take its course?

What is in a personal domain name anyway? Technically it is a unique identifier on the internet, a promise that we be discoverable within a sea of a billion internet users. As a unique identifier it is as valuable as our tax or social security number, or even our name. Personal domain names have been marketed as carving out real estate of our own on the internet, but I do not agree with this metaphor.

What is in a personal domain name anyway? Technically it is a unique identifier on the internet, a promise that we be discoverable within a sea of a billion internet users. As a unique identifier it is as valuable as our tax or social security number, or even our name. Personal domain names have been marketed as carving out real estate of our own on the internet, but I do not agree with this metaphor.A domain name can be for life but it can also change to keep up with changes in our circumstances. We can use it immediately or store it away. Hidden away personal domain names are unreachable to anybody else. Against basic intellectual property law, this is indeed one item of intellectual property that can be kept away from all humanity — a small egoistical action available to each one of us. A personal domain name can even be under-used, forced to merely forward internet users to another domain name that is more desirable to us. And, of course, it can be abandoned at any moment for somebody else to take.

Personal domain names are harsh reminders of our unique-lessness. Thousands carry the same name as us. Personal domain names are up for grabs by whoever is the fastest or better informed. Others will have to patiently wait, if ever to be rewarded or be given a second chance.

Therefore, as with any good in scarcity therein lies their true worth. A prestigious, in vogue, personal domain name adds value to the social image of its holder. Less so a less common one — and we have yet to see domain names that are looked down on.

Social image value, however, lies in the eye of the beholder: Because new domain name extensions are added periodically one has to remain alert as to what is available and, even better, trendy. Today, your name ending in “.com” is considered best. However new alternatives pop up all the time: Should we add a “.me” personal domain name as well? What about “.name”? Perhaps also a domain name with our profession in it (e.g. “.accountant”)? The list is practically endless, ultimately connected with how we see, and wish to project, our own self.

Social image value, however, lies in the eye of the beholder: Because new domain name extensions are added periodically one has to remain alert as to what is available and, even better, trendy. Today, your name ending in “.com” is considered best. However new alternatives pop up all the time: Should we add a “.me” personal domain name as well? What about “.name”? Perhaps also a domain name with our profession in it (e.g. “.accountant”)? The list is practically endless, ultimately connected with how we see, and wish to project, our own self.Personal domain names are a relatively recent concern. In the early days of the internet nobody imagined a domain name of one’s person. Speculation at best evolved around foreseeable popular domain names such as “business.com” or “sex.com”. So-called cybersquatters, a term derived again from the real estate domain, only purchased domain names of famous companies in order to resell them with a handsome profit. Nobody ever imagined registering personal domain names for their own use, much less for their children.

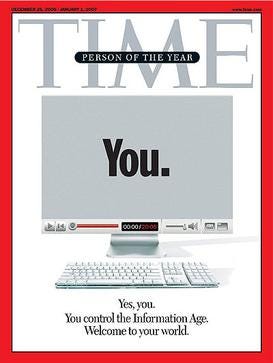

It was most likely the 2006 Time Magazine “You” person of the year article that first brought to our attention that each one of us is the product. And, for any product to have any luck in modern society good marketing is imperative. Social media presence aside, a prestigious personal domain name and a corresponding good-looking personal website is the starting point and at the same time the point of reference upon which such a personal promotional policy builds.

Apparently however one needs to be worth of one’s domain name. If you wish you to be the only one carrying a domain name of your name among the thousands or even millions that carry the same name as you, well, then you better deserve it. Keeping a prestigious personal domain name is meritocracy on the internet: One can only support it through a correspondingly long list of achievements.

However, this is exactly where the real problems kick-in: If you are unlucky enough to be named Mark Zuckerberg, can you really claim the domain name “markzuckerberg.com”? Even worst, if your kid happens to carry the same name as the then President of the USA or the next trendy multi-billionaire, could it still keep the “.com” personal domain name you so prudently acquired for it at its birth? Even my own (rare) name is shared not only by Greece’s most famous singer but also by a prominent line of politicians and lawyers. What gives me the moral (not legal, legal is served on the first come-first served principle) to keep my name’s “.com” domain name against them?

This is why I never quite liked the real estate metaphor: A moderately priced real estate may be bought and kept for life by anybody. A 30-Euro/per year personal domain name may be bought by anybody, but it can well come to be that he or she at some point will simply feel not entitled to keep it any longer.

Even if this is not the case, a locked away domain name can be depressing. Asset idleness makes us restless. A personal domain name without a good-looking, updated personal website is our next project waiting to take place, tormenting us until it does, particularly if its start is endlessly postponed towards an unforeseeable future.

So, in view of the above, should we buy one, or more, for our children?

Thales replied to Solon that he remained single because he did not like the idea of having to worry about children; Parenting had always been a demanding job. While our basic instinct is to equip our children as best as possible so as to navigate life successfully (which after all led to a field of law, on inheritance rights, as old as humans), exactly how is that to take place has long been a point of debate.

A thousand years ago unwillingness to divide (low yield) land dictated that only the firstborn inherited all assets, leaving children next in line to hope for a military career, priesthood, or a good marriage. Kant’s emancipation through knowledge made things easier for second-borns, and I think that the rise of intellectual property finally made life a level playing field. Or, perhaps this is not true any longer: The Economist recently spoke of an “hereditary meritocracy”, whereby upper classes pay more (attention) to their children’s education, leading to the creation of an intellectual capital that is transformed later on into tangible property.

So, are personal domain names with our children’s names part of the intellectual property to be inherited to them, together with a good education and all our other social capital (our own name and reputation and social network), in order for them to perform better in their lives? Only two decades ago Magris wrote that he had been collecting Meissen porcelain sets piece-by-piece for years, in order to pass them on even as half-sets to his children thus allowing them to start their own collection. In an IKEA world, are personal domain names for our children the Meissen porcelain sets equivalent?

I think that the problem with Meissen porcelains is that they need to be used in context. Magris can well use them to serve his guests, however if one is found with an inherited Meissen set whereby however his or her other life circumstances do not concur, then that porcelain set risks becoming a depressing relic of a past life that was but no longer is, of a life that could be, of an unfulfilled promise or, even worst, potential.

Why would anyone wish to inflict so much pain to his or her children? I suppose there are two ways of seeing this, the aggressive one, whereby setting the bar high incentivises, and the passive one, whereby parent’s ambitions should not be imposed upon their children in fear of failure. Coming from a European background I would tend towards the latter but I can well understand proponents of the former.

So, I did not buy domain names with my children’s names after all. Technological developments aside (that in one sweep could easily render all today’s domain name system obsolete), I believe it is a matter of expectations. I choose not to impose on my children what I think they should do, what I think they should accomplish. Nor set them on a constant struggle to justify keeping their personal domain name against all others. I would prefer not to set any expectations for them whatsoever. However, I fully understand those parents that think different, and, for example, choose to place a bet on their infant sons making the national team before they reach thirty — after all, quite a few of them got a nice pay-check out of their blind faith to their offspring’s potential.