The (New) Role of States in a ‘States-As-Platforms’ Approach

Published in the Constitutional Discourse blog, 28.01.2023

The forceful invasion of “online platforms” not only into our everyday lives but also into the EU legislator’s agenda, most visibly through the DSA and DMA regulatory initiatives, perhaps opened up another approach to state theory: what if states could also be viewed as platforms themselves? Within the current digital environment online platforms are information structures that hold the role of information intermediaries, or even “gatekeepers”, among their users. What if a similar approach, that of an informational structure, was applied onto states as well? How would that affect their role under traditional state theory?

The ‘States-as-Platforms’ Approach

Under the current EU law approach, online platforms essentially “store and disseminate to the public information” (DSA, article 2). This broadly corresponds to the digital environment around us, accurately describing a service familiar to us all whereby an intermediary offers to the public an informational infrastructure (a “platform”) that stores data uploaded by a user and then, at the request of that same user, makes such data available to a wider audience, be it a closed circle of recipients or the whole wide world. In essence, the online platform is the necessary, medium to make this transaction possible.

Where do states fit in? Basically, states have held the role of information intermediaries for their citizens or subjects since the day any type of organised society emerged. Immediately at birth humans are vested with state-provided information: a name, as well as a specific nationality. Without these a person cannot exist. A nameless or stateless person is unthinkable in human societies. This information is subsequently further enriched within modern, bureaucratic states: education and employment, family status, property rights, taxation and social security are all information (co-)created by states and their citizens or subjects.

It is with regard to this information that the most important role of states as information brokers comes into play: states safely store and further disseminate it. This function is of paramount importance to individuals. To live their lives in any meaningful manner individuals need to have their basic personal data, first, safely stored for the rest of their lives and, second, transmittable in a validated format by their respective states. In essence, this is the most important and fundamental role of states taking precedence even from the provision of security. At the end of the day, provision of security is meaningless unless the state’s function as an information intermediary has been provided and remains in effect—that is, unless the state knows who to protect.

What Do Individuals Want?

If states are information brokers for their citizens or subjects what is the role of individuals? Are they simply passive actors, co-creating information within boundaries set by their respective states? Or do they assume a more active role? In essence, what does any individual really want?

Individuals want to maximise their information processing. This wish is shared by all, throughout human history. From the time our ancestors drew on caves’ walls and improved their food gathering skills to the Greco-Roman age, the Renaissance and the Industrial Revolution, humans basically always tried, and succeeded, to increase their processing of information, to maximise their informational footprint. Or in Van Doren’s words “the history of mankind is the history of the progress and development of human knowledge. Universal history […] is no other than an account of how mankind’s knowledge has grown and changed over the ages”.

At a personal level, if it is knowledge that one is after then information processing is the way of life that that person has chosen. Even a quiet life, however, would be unattainable if new information did not compensate for inevitable change around us. And, for those after wealth, what are riches other than access to more information? In essence, all of human life and human experience can be viewed as the sum of the information around us.

Similarly, man’s wish to maximise its information processing includes the need for security. Unless humans are and feel secure their information processing cannot be maximised. On the other hand, this is as far as the connection between this basic quest and human rights or politics goes: increase of information processing may assumedly be favoured in free and democratic states but this may not be necessarily so. Human history is therefore a long march not towards democracy, freedom, human rights or any other (worthy) purpose, but simply towards information maximization.

The Traditional Role of States Being Eroded by Online Platforms

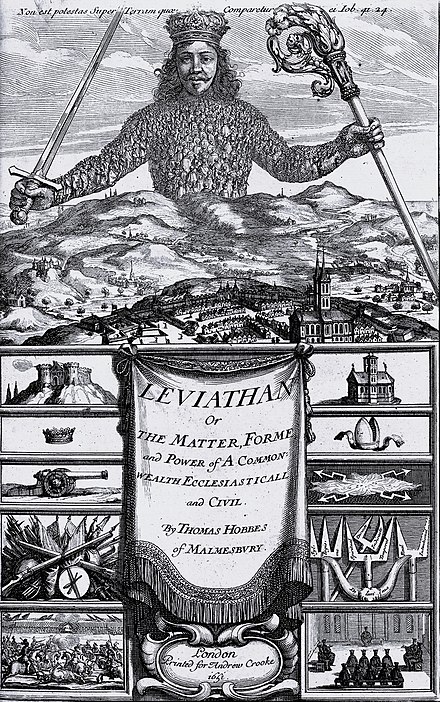

Under traditional state theory states exist first and foremost for the provision of security to their citizens or subjects. As most famously formulated in Hobbes’ Leviathan, outside a sovereign state man’s life would be “nasty, brutish, and short” (Leviathan, XIII, 9). It is to avoid this that individuals, essentially under a social contract theory, decide to forego some of their freedoms and organise themselves into states. The politics that these states can form from that point on go into any direction, ranging from democracy to monarchy or oligarchy.

What is revealing, however, for the purposes of this analysis in Hobbes’ book is its frontispiece: In it, a giant crowned figure is seen emerging from the landscape, clutching a sword and a crosier beneath a quote from the Book of Job (Non est potestas Super Terram quae Comparetur ei / There is no power on earth to be compared to him). The torso and arms of the giant are composed of over three hundred persons all facing away from the viewer, (see the relevant Wikipedia text).

The giant is obviously the state, composed of its citizens or subjects. It provides security to them (this is after all Hobbes’ main argument and the book’s raison d être), however how is it able to do that? Tellingly, by staying above the landscape, by seeing (and knowing) all, by exercising total control over it.

Throughout human history information processing was state-exclusive. As seen, the only thing individuals basically want is to increase their processing of information. Nevertheless, from the ancient Iron Age Empires to Greek city-states, the Roman empire or medieval empires in the West and the East, this was done almost exclusively within states’ (or, empires’) borders. With a small exception (small circles of merchants, soldiers or priests who travelled around) any and all data processing by individuals was performed locally within their respective states: individuals created families, studied, worked and transacted within closed, physical borders. There was no way to transact cross-border without state intervention, and thus control, either in the form of physical border-crossing and relevant paperwork or import/export taxes or, even worse, mandatory state permits to even leave town. This was as much true in our far past as also recently until the early 1990s, when the internet emerged.

States were therefore able to provide security to their subjects or citizens because they controlled their information flows. They knew everything, from business transactions to personal relationships. They basically controlled the flow of money and people through control of the relevant information. They could impose internal order by using this information and could protect from external enemies by being able to mobilise resources (people and material) upon which they had total and complete control. Within a states-as-platforms context, they co-created the information with their citizens or subjects, but they retained total control over this information to themselves.

As explained in a recent MCC conference last November, online platforms have eroded the above model by removing exclusive control of information from the states’ reach. By now individuals transact over platforms by-passing mandatory state controls (borders, customs etc.) of the past. They study online and acquire certificates from organisations that are not necessarily nationally accredited or supervised. They create cross-national communities and exchange information or carry out common projects without any state involvement. They have direct access to information generated outside their countries’ borders, completely uncontrolled by their governments. States, as information brokers profiting from exclusivity in this role now face competition by platforms.

This fundamentally affects the frontispiece in Leviathan above. The artist has chosen all of the persons composing the giant to have no face towards the viewer, to face the state. This has changed by the emergence of online platforms: individuals now carry faces, and are looking outwards, to the whole wide world, that has suddenly been opened-up to each one of us, in an unprecedented twist in human history.

The New Role of States

If the generally accepted basic role of states as providers of security is being eroded by online platforms, what can their role be in the future? The answer lies perhaps within the context of their role as information intermediaries (a.k.a. platforms), taking also into account that what individuals really want is to maximise their information processing: states need to facilitate such information processing.

Enabling maximised information processing carries wide and varied consequences for modern states. Free citizens that are and feel secure within a rule of law environment are in a better position to increase their informational footprint. Informed and educated individuals are able to better process information than uneducated ones. Transparent and open institutions facilitate information processing whereas decision-making behind closed doors stands in its way. Similarly, information needs to be free, or at least, accessible under fair conditions to everybody. It also needs to remain secure, inaccessible to anybody without a legitimate interest to it. Informational self-determination is a by-product of informational maximisation. The list can go on almost indefinitely, assuming an informational approach to human life per se.

The above do not affect, at least directly, the primary role of states as security providers. Evidently, this task will (and needs to) remain a state monopoly. Same is the case with other state monopolies, such as market regulation. However, under a states-as-platforms lens new policy options are opened while older assumptions may need to be revisited. At the end of the day, under a “pursuit of happiness” point of view, if happiness ultimately equals increased information processing, then states need to, if not facilitate, then at least allow such processing to take place.