Fact-checking on the Internet: Do we still need encyclopedias?

Published on Medium, 28 January 2019, as part of the Digitalia Moralia series.

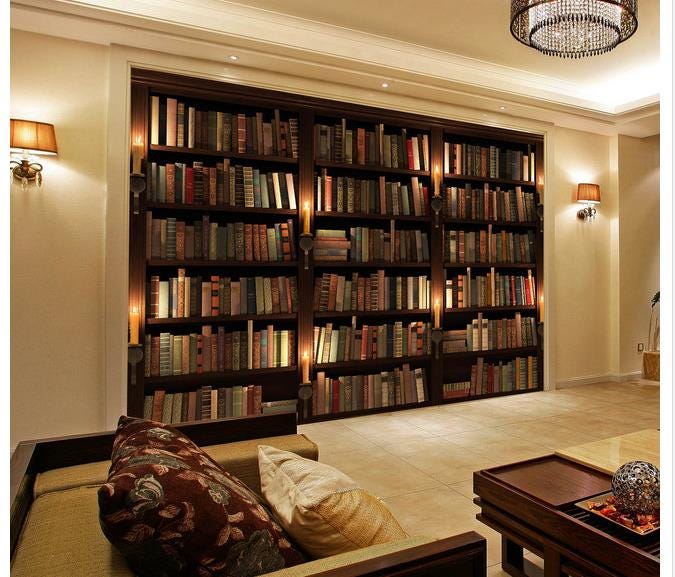

Patrick Leigh Fermor designed his house in Kardamyli in such a manner that next to the dining room would be placed large collections of encyclopedias and reference books, in order to quickly resolve any dispute among his guests. The first Guinness Book of Records was published back in 1954 to serve more or less similar purposes. And, I can think of no authors of the past who did not admit to keeping a few dictionaries on their desk while working on their craft.

Similar was the case with all aspiring middle-class households: An encyclopedia was an essential household component, purchased immediately after the electronic appliances and well before the second television set or the VCR. When I was young these encyclopedias were sold by well-meaning door-to-door salesmen, and were paid for in monthly installments that seemed to last for a lifetime — both a long-term investment for each member of the family and a social status symbol to be casually visible to family guests in the living room.

Impulsive fact-checking is a natural human need: Leather-bound encyclopedias and reference books were stockpiled in the libraries of the elites; Annual Guinness Books of Records were purchased by pubs. However, within twenty-years internet search engines made all of that redundant. Now any question can be answered within seconds by simple use of a smartphone. My dictionaries are gathering dust on the shelves next to my desk while I work keeping multiple tabs with online dictionaries open and running the occasional internet search on top of that.

Those businesses that were hit by the change had to quickly adapt. Essentially all reputable encyclopedias and dictionaries moved online.

Was this a change without consequences? I think that quality was hurt. Encyclopedias, while on-paper and expensive, ideally outsourced the analysis of each entry to an expert in the respective field. Their list of entries itself was conscious.

None of these is a necessary condition on the internet. In an age of platforms and crowd-sourcing in most cases work is expected to be carried out by the users. Nevertheless, crowd-authoring, while efficient, lies more often than not far from quality work (this is, after all, why good academic work is still appreciated). And, self-choice of entries lies dangerously close with online social networking.

However, the immediate benefits of this change to human interactions are plain for all to see. Instead of endless disputes and sullied guests a final answer is within reach. In this way time may be spent in more fruitful conversation. Is that indeed the case? One can never know — and cannot reasonably expect all coffee-house and dinner-table discussions to turn to philosophy. Nevertheless, I feel that overall there is clear benefit. For example, if a piece of music or a text is disputed, rather than endlessly arguing about it time can be spent to replay it online, reminding us thus why the discussion started in the first place.

Would that be all? I fear not. Once used extensively in this manner, the internet may be confused with a know-it-all machine. This risk is higher in my generation, that was not raised with it but has adopted the internet with the uncritical enthusiasm of the neophyte. Although a mention on the internet means very little in terms of truthfulness, most people today take the internet at face value, believing whatever they find on it.

In the past authority informed everybody what was true. Whatever was in the encyclopedia had to be the indisputable truth. Such authority was passed from the paper to the airwaves: Television enjoyed it for several decades, a voice from above speaking the truth. This transfer of authority was naturally passed to the internet.

However the problem with the internet is the exponential multiplication of voices. The internet allows everybody to be heard on equal terms with others. On the internet there is no distinction between a voice from Hyde Park’s Speakers’ Corner and an MP in the House of Commons.

While this can be seen by some as egalitarian and liberating and by others as nihilistic and reactionary, if there is any lesson the Internet has already taught us is that there is no truth. Apart from the simplest of facts (e.g. release date or director of a film) any qualitative addition (such as, “who was the first to”) turns things back to the original mess. Qualitative additions can blur even the simplest of questions — try running a “world’s largest pizza” internet search to see how this is possible.

If simple facts are hard to establish one can easily imagine that ideas and politics are nearly impossible to agree on with or without the internet. Enter, then, the “fake news” saga.

Where does this leave us? Humans are not supposed to function without authority, if we are at least to take Aristotle’s word on this. Intellect rules strength, and hence hierarchies in human societies are “natural”. Cicero would most likely agree to that: “Why, even if they gave no reasons, they would convince me by their very authority”.

How has authority been affected by the internet?

In the past intellectual authority was connected with education. Rich Athenians got their offspring the best education the city could offer, be it by educated slaves or well-paid sophists (it was the guys that got to the nerves of Socrates because of their marketing policies). In Rome study tourism thrived, with the children of the well-off travelling all across the empire to spend a year or two with the best philosopher-teachers money could buy. Universities, since the 11th century, organised such coming and going better by pooling resources, and today a prestigious university title can take you a long way in business or politics or even in aimless discussions under a summer moon.

However the internet threatens this model. If fact-finding is only a smartphone away what is the need for education on anything different than effective internet searching? If even the most prestigious universities offer courses and degrees online, what is the need to actually go there to study?

More substantially, if everything can be challenged through a simple internet search what is the need for an authority? Under such circumstances an authority may sound pompous and arrogant, ruining everybody’s summer evening — hence the “elitism” accusation, to complete the destruction of any hard-earned degree.

In other words, by empowering the individual the internet has overturned the intellectual authority model of ages. One does not need huge volumes of encyclopedias and dictionaries nor four-years higher education: A smartphone and an internet search will do just fine.

To make things even worse, anybody can find his or her truth on the internet. Multiple sources make findings inconclusive. Too many voices wreak havoc. In essence, however, the internet search comes full circle, giving anybody arguing anything the opportunity to find exactly the truth he or she wanted to find in the first place. The internet only adds authority to it.

This is where we are right now. It has not yet been understood that the internet merely replicates on the digital what is known on the physical: In this case, as many opinions as can be heard in a pub brawl. In our search for truth the internet today only adds authority to what we already want to hear. It is not an encyclopedia it is merely our sidekick.

Authority then will soon be needed again, at least if any credit should go to the ancient masters. I suppose that this will happen as soon as everybody is ready to laugh at another’s “I found it on the internet” claim. I do not know the form that this new authority will take. Presumably, if past experience can be used, it will be paid-for information that will be unanimously considered better than information openly available on the Internet. Which, in turn, brings us back to good reference books and encyclopedias, making thus a full circle back to the, digital this time, living rooms of the elites.